If you think about asbestos at all, it’s probably as a construction material in old buildings, something that’s being carefully monitored and controlled. You almost certainly aren’t thinking of it in the present tense, let alone as a danger in the products we buy everyday. Yet the outcome of a recent lawsuit reflects the realities of asbestos as an ongoing problem, and the ease with which some businesses can skirt safety laws.

A legal case involving cosmetics giant Johnson & Johnson has proved a victory for asbestos campaigners, but it also reflects the barriers that remain in the fight to eradicate asbestos. If a product can be sold on the mass market containing asbestos right into the modern era, where else could it be hiding – and what chance do we really have of getting rid of it?

A landmark victory

The case resolved by Johnson & Johnson has dogged the company for more than four years now. The company was taken to court by thousands of people in the US, many of them women who had come into contact with its talc-based baby powder. Laboratory testing had revealed that some samples of the baby powder contained asbestos, which frequently contaminates natural talc deposits.

Johnson & Johnson has now settled many of the cases for a combined total of $2.1 billion – and most notably, has just removed its talc-based baby powder from sale worldwide. The company had previously removed it from sale in many countries due to safety concerns, with the United States and United Kingdom being notable exceptions. Johnson & Johnson has managed its liabilities by forming a new company to shoulder the burden and then declaring it bankrupt, a process that is legal and has been ratified in Texas.

The trial was an arduous and damaging one for the company. Among the many revelations was a study funded by Johnson & Johnson in the 1970s, in which prisoners were injected with two forms of asbestos in order to determine its safety compared to talc. An attempt by the company to appeal $2.1 billion in damages failed, as did efforts to prevent another lawsuit alleging that it hid evidence about the dangers of asbestos.

Why asbestos is still a threat

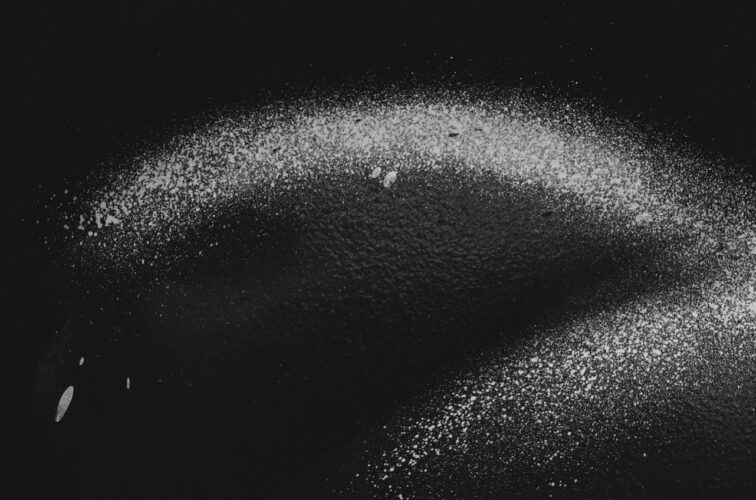

The dangers posed by asbestos in baby powder should be obvious. The clouds the powder produces when used can be inhaled by both parents and children, putting both at risk of asbestos-related diseases. While the white asbestos in talc is the least dangerous form, there is no safe form, and no safe level of exposure.

Any amount of asbestos increases the risk of developing cancers such as lung cancer, ovarian cancer and mesothelioma, many of which are extremely deadly, or even incurable. And while the latency period for many asbestos-related diseases can be up to 30 years, this clearly impacts children more than adults – making the presence of asbestos in baby powder a particularly horrifying reality.

What this case reflects is a gap between our general attitudes towards asbestos and the realities of asbestos today. While it isn’t widely used in products, it can still sneak its way into things like cosmetics and car parts due to its continued legality in other parts of the world, as well as lax safety standards. And even as these products continue to evade quality controls, asbestos still lingers all around us – and poses a growing risk to health.

A ticking time bomb

The UK used more asbestos than any country in the world as a result of post-war reconstruction. While some asbestos has been removed since, it still remains in thousands of buildings, largely in the form of asbestos-containing materials (ACMs) such as tiles and asbestos insulating board (AIB). Despite all of this, action and awareness on asbestos today are both low. It’s perhaps also notable that the UK was one of only a few western markets where talc-based baby powder was still sold, as opposed to talc-free baby powder alternatives.

There can be no doubt that asbestos removal can be costly, and that this burden will have to be shouldered by someone. But the risk of asbestos exposure grows the longer ACMs persist, and particularly when they go unobserved. Asbestos ultimately remains a present danger because there is a lack of both money and political will to get rid of it. Most asbestos is now 50 or more years old, and the general advice – that it’s safer to leave it in place than remove it – only works when cataloguing and inspections perform their intended function.f

HSE inspectors need to ensure that asbestos is being regularly assessed for damage, and maintained properly. Yet low inspection numbers and reductions in funding suggest that this isn’t the case. Asbestos is also only catalogued in public buildings and business premises, with no requirement to record or ensure the maintenance of asbestos in private properties. On top of this, rogue builders commonly upset this with little reprimand for exposing people to the deadly substance, either going unnoticed or paying small fines.

The victory over a huge multinational corporation by campaigners demonstrates that action on asbestos is achievable, and should improve awareness around asbestos. The knowledge that asbestos hasn’t gone away – and was actually in products being sold until now – should help people to question whether this is the only area in which asbestos remains a concern. With luck, this will help embolden campaigners who have been working tirelessly to end asbestos with little public fanfare – and lead to a public clamour for greater political action.