While climate change remains at the forefront of the environmental agenda, concerns have been growing around plastic waste. Powerful documentaries such as Planet Earth 2 have shed a light on the magnitude of plastic waste in our oceans, and the devastating effect it is having on wildlife.

While companies are increasingly looking to cut down on plastic waste, some claim that current efforts don’t go far enough. The evidence is growing that plastic waste isn’t just an immediate threat to wildlife, but a ticking time bomb for our own health – a poison that’s comparable to the environmental disaster of asbestos.

A deadly legacy

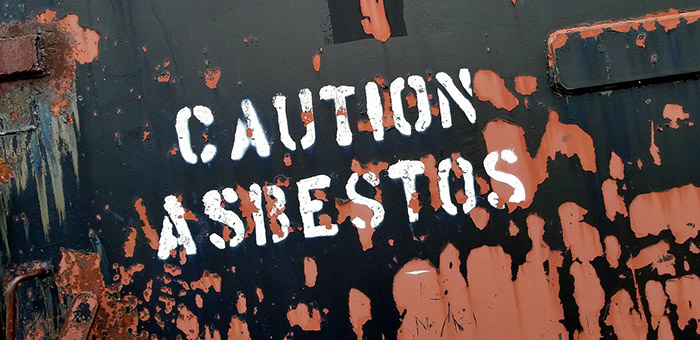

Asbestos is widely known as a dangerous substance now, even if it still persists in historic buildings around us. From being widely adopted in the early to mid 20th century, the 1970s and 80s saw growing evidence of the dangers of asbestos, and the start of efforts to restrict its use. All forms of asbestos weren’t banned in the UK until the year 2000, by which point it had claimed thousands of lives.

Once considered a miracle substance for its ability to resist fire and electricity, it was found that asbestos released microscopic fibres when disturbed, which were absorbed into the lungs. The jagged particles permanently damaged cells in the lungs, causing not only serious breathing problems, but the development of a unique and dangerous form of cancer.

It’s hard to imagine that plastic, which we use and encounter on a daily basis, could have anything like the deadly impact of asbestos. Yet the evidence is mounting that the two substances could have more in common than anyone expected. What it comes down to is how resistant they are to biodegradation – and what those tiny particles do when absorbed by people and animals.

Hidden dangers

We think of plastic as something that’s often tough and generally resistant to damage, and to a large extent that’s true. That’s part of the problem with plastic waste, as when it enters the ocean or other environments, it can take thousands of years to degrade, meaning that it just accumulates and pollutes indefinitely. But that’s not to say that plastic doesn’t degrade at all: it just does so very slowly.

Like asbestos, plastic is worn away over time into tiny microscopic particles called microplastics. These bits of plastic can become so small that they have the potential to be absorbed into cells, similar to tiny asbestos fibres. Once there, they can cause damage that leads cells to mutate, causing cancers and affecting the cells in other ways.

The exact nature or extent of this damage is under research, and remains highly disputed. But the increasing use of plastics does correlate with an increase in a number of diseases and syndromes. Cancers of all kinds are increasing over time, as is infertility. The manufacture of plastics also involves chemicals which are known to be harmful, which leech into our bodies when microplastics are absorbed.

Assessing the damage

The impact of asbestos was easy to measure because the damage, for those exposed to heavy concentrations, was extremely easy to correlate. The disturbance of asbestos in mining and production meant that large amounts of it were inhaled, and damage could be quick to manifest. Over time, we’ve learned that asbestos related diseases can take up to 50 years to appear – but the disease they cause is so unique that it’s easy to identify the culprit.

With plastics, this isn’t so simple. Not only are there 13 common types of plastic polymer, but the fact that they are hard wearing (and can’t be breathed in like asbestos) means the effects are much harder to trace. Scientists have shown the effect of heavy particle pollution on animals such as crustaceans, but the levels most people are exposed to are lower, and are happening over the course of our entire lives.

What isn’t in doubt is that microplastics entering our bodies cannot be a good thing. The assumption was always that they went through our systems without being absorbed in any great quantity. Now that we know they are entering our blood streams and organs – and staying there – the question is not whether they are causing damage, but how much, and how we can remedy this in the short and long term.

Plastics have been around for long enough and in great enough qualities to determine that their effect on our bodies isn’t as catastrophic as the most serious forms of asbestos, at least in the short term. But there is a real question as to how exposure to microplastics compares to occupational exposure to white asbestos. While the research is still tentative, the suggestion that plastics may be entering cells throughout the body – and causing a raft of different cancers – is at least as troubling as mesothelioma.

Two things are abundantly clear: that the effect of plastic pollution on the environment is overwhelmingly negative, and that the effect of microplastics on our bodies cannot be positive. This should be enough for us to accelerate the phasing out of plastics in as many areas as possible, particularly single use plastics. This will be driven by governments and corporations, but weeding out plastics from your daily routine will go a long way to encouraging them – and potentially extending lives in the future.